Each summer, the first day of our family visit to London was always a stroll through Piccadilly with Alex. Laura and Chris, uneasy travellers by plane, were shaking off their jet lag in our hotel room.

Across the broad boulevard, facing Green Park tube station, stood the venerable Ritz Hotel. To me, once an immigrant to the United Kingdom, it was an inspiration that a Swiss hotelier could leave such an imprint on British heritage. To Alex, born an equal in Canada, The Ritz presented an altogether different connotation. As I took a moment to contemplate, Alex fished out his iPhone and busily snapped photos from every angle of the hotel and its frock-coated yeomen. To him, it was yet another quaint edifice to be photographed and instantly transmitted to friends across the globe.

“Pops, I’m off to Ralph Polo. I’ll meet you later.”

What could I say? I shrugged and consulted my watch. “It’s 4.30. How about meeting back at six? At Hatchards?”

Alex nodded. In the blink of an eye, he was gone, leaving his father to retrace their annual pilgrimage alone.

Having paid my respects to The Ritz, I strolled down Piccadilly to my next port of call—the Alliance sculpture on Bond Street.

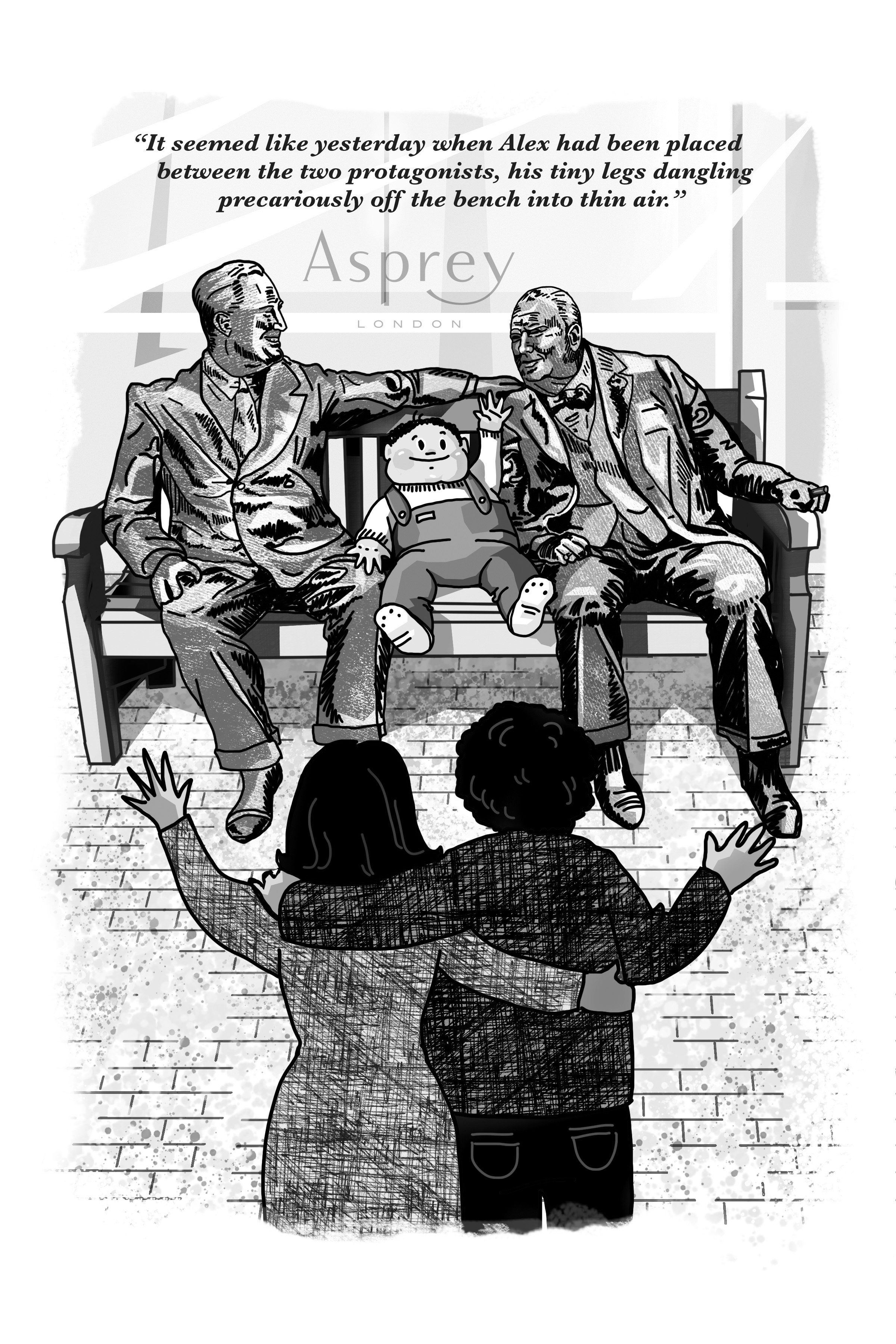

The statue, a celebration of the special relationship between Britain and the USA during the Second World War, comprised a bench on which sat Churchill and Roosevelt, petrified in bronze. The Prime Minister held a smoking cigar between his fingers, levering himself off one corner. The rest of him leaned forward towards his friend. The President, seated at the other end of the bench, had the length of his arm resting on the back, smiling as though sharing a joke.

It seemed like yesterday when Alex had been placed between the two protagonists, his tiny legs dangling precariously off the bench in mid-air. Today, there would be no way he could be fitted between them—his spindly legs would stretch along the pavement. Besides, nowadays Alex shunned family photos. Yet his Facebook was full of images of himself surrounded by friends in activities ranging from barbecues to mountain climbing. I accepted Alex’s aversion to family photos—I had hardly a handful from my own childhood. It was the happiness in abundance expressed in those pictures that cut me. Perhaps I coveted the circle of friends Alex had assembled around him—an ability lost to his father as he negotiated from one unsettling environment to the next. By the time I had stabilised my life in Canada, I considered myself too old to risk opening up as I might have done at Alex’s age.

Behind the Alliance stood Asprey, crown jeweller to the Royal Family for generations. It was here that Prince Charles purchased an engagement ring for Diana, his future consort.

Asprey displayed its wares in small, discreet window cabinets jutting from its white walls. I remembered my first visit here with Alex. My son had stood on tiptoe, his hands clutching the window frame to glimpse the treasures within, still unable to see—until his father lifted him onto his shoulders. Now the son was a foot taller than his father.

Today, the Aladdin’s trove of precious gems and watches lay on maroon velvet beneath probing beams of light. Varicoloured diamonds and finger-sized green emeralds coruscated and enticed. Someone had rolled individual pearls—from milky white to stunning gold—headlong into a necklace of silky grey pearls. As Alex grew up, father and son would venture into the revered establishment pretending to buy a gift for Laura. Without Alex, I didn’t have the audacity to enter Asprey and grandstand.

Time was running out. I still wanted to buy Alex a present. With that in mind, I jog-trotted two blocks, darting into Burlington Arcade.

Built in 1818, the arcade was one of London’s first and finest shopping centres. Its fifty-odd exclusive boutiques were clustered along a narrow walk, barely eight feet wide, covered by a long series of V-shaped glass roofs. From one end to the other, the structure was supported by carved marble arches. But I had no time to marvel. A beadle, accoutred in top hat and dark frock coat overhung with yards of white brocade, eyed me with suspicion as I glided past and into Vilebrequin, the world’s master purveyor of swimwear. Sink or swim, I was determined to break Alex’s mould of monochrome clothing. Vilebrequin was famous for the brightest and boldest swimming trunks ever seen. One caught my eye—in shocking purple with iridescent tortoises in shades of mandarin orange and jade green. I gulped at the price. Well, if Alex didn’t approve, he could always gift it to his brother.

A few minutes’ walk along Piccadilly, sandwiched between a store selling hunting whips and an Italian bistro, stood my favourite bookstore—Hatchards. It was like stepping into Dickens’s Old Curiosity Shop. Its musty rooms were a warren of heavy, dark wood, their portent magnified by ancient, shadowy lighting. I spotted the latest John le Carré offering—the author reading The Pigeon Tunnel. Alex would love it—one of the few interests we shared. As I surrendered my Visa card, the wall clock chimed six and Alex entered—on time, as always.

I wondered if Alex had remembered me whilst shopping, as I had done him. Amid his frenetic lifestyle, I wasn’t sure if Alex ever thought of us. It seemed the breeding and upbringing of children was passé—a thankless task taken for granted by the very children upon whom so much love, energy, and time was lavished. I sighed, turning from my reverie, as though disengaging a radio, then walked, smiling, towards my son.

“Pops! Look what I got you.”