Who was this man?

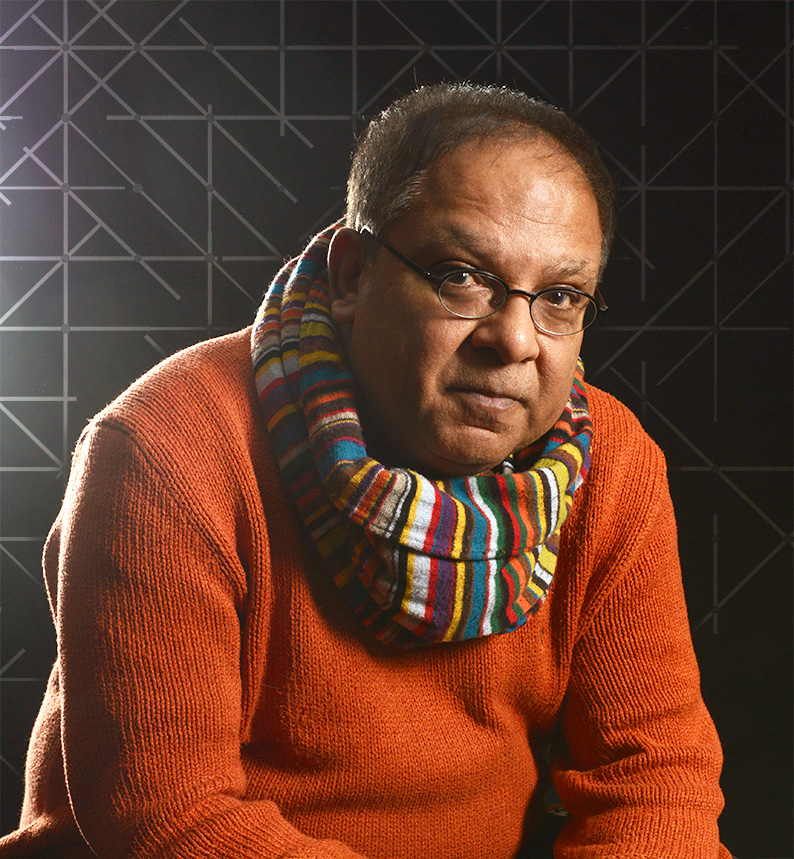

He was unshaven, with no tie, his shirt collar open and missing buttons. He seemed to have slept in his clothes. His suit was wrinkled and creased. He had the eyes of a hunted animal. This wasn’t Dad… was it? Dad had always worn a suit and tie. He took so much pride in his appearance, always sporting a million-dollar smile.

Laura and I spoke out to Dad at the same time. Dad couldn’t hear us. Since his school days, when teachers would slap him around the ears, he had been nearly totally deaf. Powerful hearing aids had helped him, but now they were gone. I stared at Dad, then at my wife, wondering what to do.

My wife came to the rescue. She found a pen and, on the back of an envelope, wrote: We’re taking you home with us.

Seeing the fear in Dad’s eyes, Laura wrote again: Only for tonight, to babysit the boys. Dad acquiesced.

The next morning, I was on the phone with Calgary Social Services, trying to make an urgent appointment.

By the afternoon, Dad and I were seated before a prim, bespectacled woman in her late thirties.

She asked Dad his name and date of birth. Dad stared beseechingly at me. He took both hands, pointing them at his ears and rotating his wrists, indicating he could neither hear nor understand her.

Dad was given a written eight-question test. He threw it away and withdrew into a corner, repeating, “I don’t know. I don’t know. I want to go home.”

The assessor asked me, “Do you have guardianship or power of attorney over your father?”

“No.”

“We can do nothing without a doctor’s letter attesting to his physical and mental capacity. We can’t test him as he’s deaf. How long has he been like this?”

“Don’t know. We were away for Christmas in the Bahamas.”

She gave me a sardonic look. “There’s a three-year waiting list for accommodation at a seniors’ lodge. Even longer for a locked facility for dementia.”

I stood up. “We can’t wait that long. Dad’s been given an eviction notice. He has three weeks to move out. He can’t stay with us.”

A few hours earlier, I had slipped out to meet a client, leaving Dad snoozing in the sitting room while Laura cooked in the kitchen. Within minutes of my leaving, Dad woke up, opened the door, and wandered out into the street. It took Laura an hour to find him.

Because of his deafness, Dad had an astonishingly loud voice. “I want to go home. Take me home,” he repeated again and again.

“Get a letter from your father’s doctor recommending a mental assessment. Have your father authorize you as his legal guardian and give you his power of attorney. You are his only child?” As she asked, I glanced at Dad, regretting— for once— that I had no siblings to turn to.

Dr. Mitha had treated us for years. He had also come from Dar es Salaam and had known Dad since then. The doctor completed his recommendation within the hour.

Ali, our lawyer, had been a close family friend for decades. Ali came home and spoke to Dad. Dad didn’t recognize him. With infinite patience, during brief moments of lucidity, Ali managed to get Dad to sign the necessary documents. With the stroke of a pen, Dad handed total control of his life, irredeemably, to me. Gone was the freedom that Dad had clung to all his life.

Dad had written no will. He possessed no assets of monetary worth.

Within a week, I guided my father through a battery of tests, got his teeth fixed and hearing aids restored, and made sure Dad had the medicine to slow his dementia.

Coming home one evening after a day of errands with Dad, I gave Laura a progress report. “They’ve placed Dad on an emergency waitlist. There’s nothing we can do save pray they find him a place to stay. It’ll be a miracle if they do. We still need to clear out his apartment. I don’t want to do so until he’s moved out. It’ll break his heart.”

Dad had been staying with us for almost a week. He hardly spoke of his apartment. Dad was in permanent melancholia. He sat in front of our bay window, staring out at the snow-covered garden (even though it was March). Suddenly, for no reason, he would burst into tears. The only time he smiled or became animated was around his grandsons. As soon as they arrived, Dad would shout, “Boys! Boys!” He couldn’t remember their names.

The miracle arrived just as needed.

Social Services called. “We have a vacancy at Cedars. Please call them. You have twenty-four hours to inspect the home and approve it.”

We left Dad with a neighbor and dashed off to Cedars.

It was a sprawling, low-lying bungalow affair just off the main road, barely fifteen minutes away. It was old and shabby. The staff were from every third-world nation, except for their supervisor—an Irishwoman close to retirement herself. She didn’t smile, giving the impression that we were eating into her precious time.

What could we do?

At ten the next morning, we brought Dad along with a stash of clothes—suits and blazers on hangers.

“He won’t need those suits. Nor underwear. He’ll have diapers. If you can, buy some jogging pants and non-slip runners. Make sure they have Velcro tabs, not laces. No jewelry or other valuables. We’ll need a list of his medications and the schedule for taking them.”

When we left him, it was like leaving our kid at preschool on his first day. There were tears and assurances that we would be back soon.

“Dad, you’re only here for a few days for a check-up. We’ll be back tomorrow,” we assured him.

As we drove away from Cedars, the unspoken question that lingered in both of our minds was: How long will he survive there?