A restaurant review led me to The Indian Tearoom in Calgary, enticing me with “the best East Indian snacks and tea in town.”

To my surprise, the food wasn’t East Indian but East African, from Dar-es-Salaam where I was born. The tearoom reacquainted me with all my childhood favourites.

In a community devoid of television, evenings in Tanzania were spent competing in robust games of Carrom, our version of pool, with my dad, uncles, and cousins. Entering the tearoom on a rainy Friday afternoon, my eyes lit up. Someone was playing the same game. “Can I help you,” he asked.

Thus began our weekly Carrom sessions, Hamid walloping me each time. Obviously, I wasn’t as good as I thought I was. Perhaps my dad and uncles had let me win. Our games were so intense, we hardly spoke.

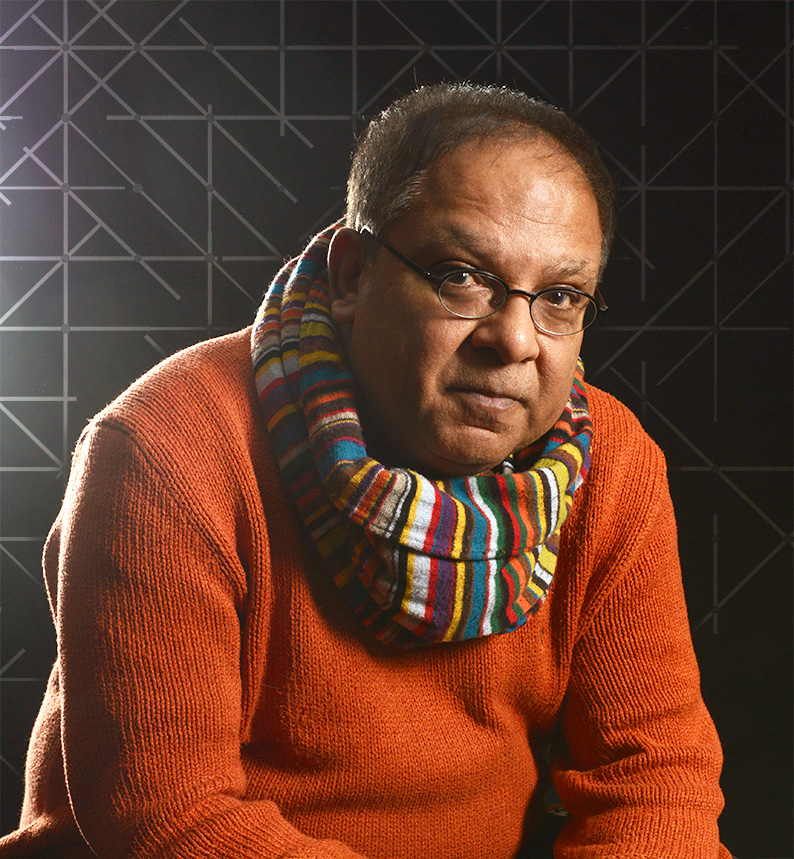

Over months, I gleaned snippets of information about my adversary—Hamid was a world-class squash player, had attended Carleton University for journalism but dropped out, he was taking a break assisting his parents who were lifelong restauranteurs—how long for, he didn’t know.

One afternoon, as I was laser-focused on a delicate off-the-cushion shot, he asked “What’re you doing tomorrow?” Highly unusual. Concentrating on my shot, I blurted, “Nothing.”

“Can you MC my wedding reception?” Having completely botched my shot, I gradually realized what he was asking. “What do you mean MC your wedding? I didn’t even know you had a girlfriend. How can I make a speech? I don’t know you.”

He smirked. “You’ll do just fine.”

Saturday arrived. Luckily, I wasn’t invited to the mosque, only to the hotel reception thereafter. The time was conveniently set at noon. The location, a few blocks from my apartment. The reception was in a hall at the back of a Holiday Inn, overlooking a swimming pool. To my chagrin, I had overslept, arriving twenty minutes late. The hall door was locked. Dressed to the nines, I had to enter the room through the swimming pool area.

The whole room stared as I sat beside the groom. All around me were dozens of tables. East Indians sat at all of them except one—the groom’s. Beside Hamid sat, not an Indian princess wrapped in a sari, but a white girl. Beside her, an elderly white woman, presumably her mother.

Hamid nudged me to make a speech. Knowing neither the groom nor his bride, I had nothing to say. In desperation, I started. “Ladies and Gentlemen, we have all known Hamid for years. Would any of you like to say a few words about him?” There was utter silence. No whispering , no hubbub, no conversation, only scowls on everyone’s face.

I plucked up my courage and turned to an Indian lady in her forties sitting at our table, praying she was an aunt.

“You must have so many stories to tell about Hamid.” Before she could refuse, I handed her the microphone, scurrying back to my seat. Silent for a minute, she rose like Medusa from her chair.

“That Hamid, lazy like anything. His parents spoil him. He waste time as journalist. For what? Now he marries white. Why not nice Indian girl?” She promptly sat down, throwing the mike on the table in disgust.

I continued to solicit a speaker. An elderly man stood up at the other end of the room. Coughing uncontrollably, he harangued Hamid for five minutes. People clapped in agreement. Now there was a line up to filch the mike. People began to shove each other. Quietude was broken asunder. I felt a storm coming, leading to fisticuffs. Quietly, I maneuvered myself backwards, tripping over someone’s handbag. As attention diverted, I turned and fled by way of the pool.

It took weeks to pluck up my courage to revisit The Indian Tearoom. Although we resumed our games, the reception was never mentioned again.

Hamid and I have been besties ever since.