It was a mistake.

Coming home one evening, I slumped into an armchair beside Mum. “Can’t go on this way. I’m so depressed. No-one at work likes me. I’m failing all my exams. How can I become an accountant when I can’t even add up? Can I go see a psychiatrist?”

At that time, there were no “counsellors”. Psychiatrists were regarded as akin to witch doctors.

“You must be mad.” She took her monogrammed notepad and scribbled down an address.” Make sure you get there Saturday at 10 a.m. And don’t be late. “With that, she dismissed me to refocus on Margaret Thatcher on the evening news.

I looked aghast at the address. It was in Golders Green, a suburb of London populated by the richest of the Jewish community. Who did Mum, a pukka working-class Muslim, know in Golders Green?

Besides, living on the outskirts of Maidenhead, it would take me hours to get there.

Somehow, I managed to cycle to the train station, catch the milk run into Paddington, change two tubes, walk a mile to find the address. By a miracle, I arrive on time.

“Don’t go to the front, but round the back and knock,” Mum had instructed.

A husky female Russian voice bade me enter. The door opened at my touch. Behind a large walnut-veneered desk sat a woman in her sixties. She had bright golden-red hair and was heavily made up. Her bosom was large, heaving under tight clothing. A light grey flimsy silk blouse complemented a garish leopard skin leotard. On the wall behind her were framed blown-up photographs of a short, thin, dapper man, always in a grey pin-striped suit and tie in the company of film stars, politicians, and other celebrities.

She stood up, towering over my five-foot-four-inch frame and clutched my hand in a wrestler’s grip. “Follow me,” she commanded.

Leading me down a corridor, she stopped in front of a door at the end. She knocked, before ushering me in. Her duty accomplished, she withdrew, closing the door behind her.

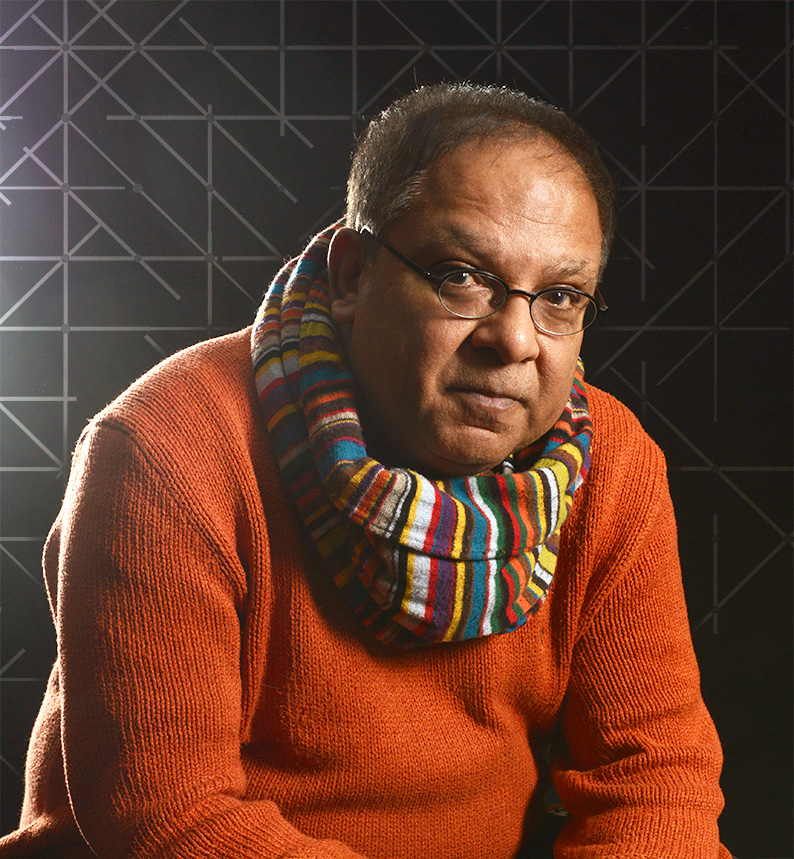

In his dark, heavily curtained sanctuary, sat the man in the photos. His standard grey suit hung shapelessly on his emaciated body. With no other lighting, a desk lamp lit up one side of his face, leaving a chiaroscuro of one half of his visage in glaring white light and the other in portentous darkness. The man rose. He was barely five foot tall. He appeared not to be Jewish, but distinctively Pakistani. What was he doing in Golders Green?

Instead of shaking my hand and introducing himself, the man ordered me to sit down opposite him and hold out my palms. Next, the man retrieved a paint roller and tray from a side drawer. The tray was filled with black paint. The man dipped the roller in, then plastered my palms with it. He grabbed my blackened hands, turned them downward and planted them firmly onto a large piece of tracing paper.

The man burst into a frenzy of activity. Opening a tin of geometry instruments, he began to draw lines across the imprints of my palms.

Breaking his solemn silence, the man bombarded me with rapid-fire questions. “When were you born?” he rasped. “Where and at what time?” all the while measuring and remeasuring the lines on my palms. Once done, he grabbed my hands and scrutinized them under his lamp. He used a large magnifying glass to compare the paper prints to my actual palms, to ensure all the fine lines had been transposed properly onto the paper.

“You’ve seen much of this world. Seen much turmoil,” he whispered in a voice out of an ancient souk, weak and wavering. “You are deeply unhappy with your life and work,” he continued. “You will encounter years more of unhappiness in both. A tumult of changes. Of constant beginnings and turbulent endings. A flight across water to a desolate land far, far away. This is not a time to waver but to endure and survive. An opportunity will come to escape…eventually. Years of misery and strife before you find peace.”

At the end, the man, still not proffering his name, asked “Any questions?”

Stunned, my head as though pounded by a sledgehammer, I could utter no words. Should I ask for a refund? Then again, I wasn’t asked to pay. How had Mum wangled this? Thinking of her, I wanted to scream. How could she do this to me, sundering any hope I had? I wanted to scream. For the love of me, the man’s words kept throbbing my brain.” Unhappiness and discontent. A journey to the middle of nowhere—an exile?” I shook my head in answer to his solicitation, walking out, cursing Mum all the way to the tube station.

The predictions all came true.