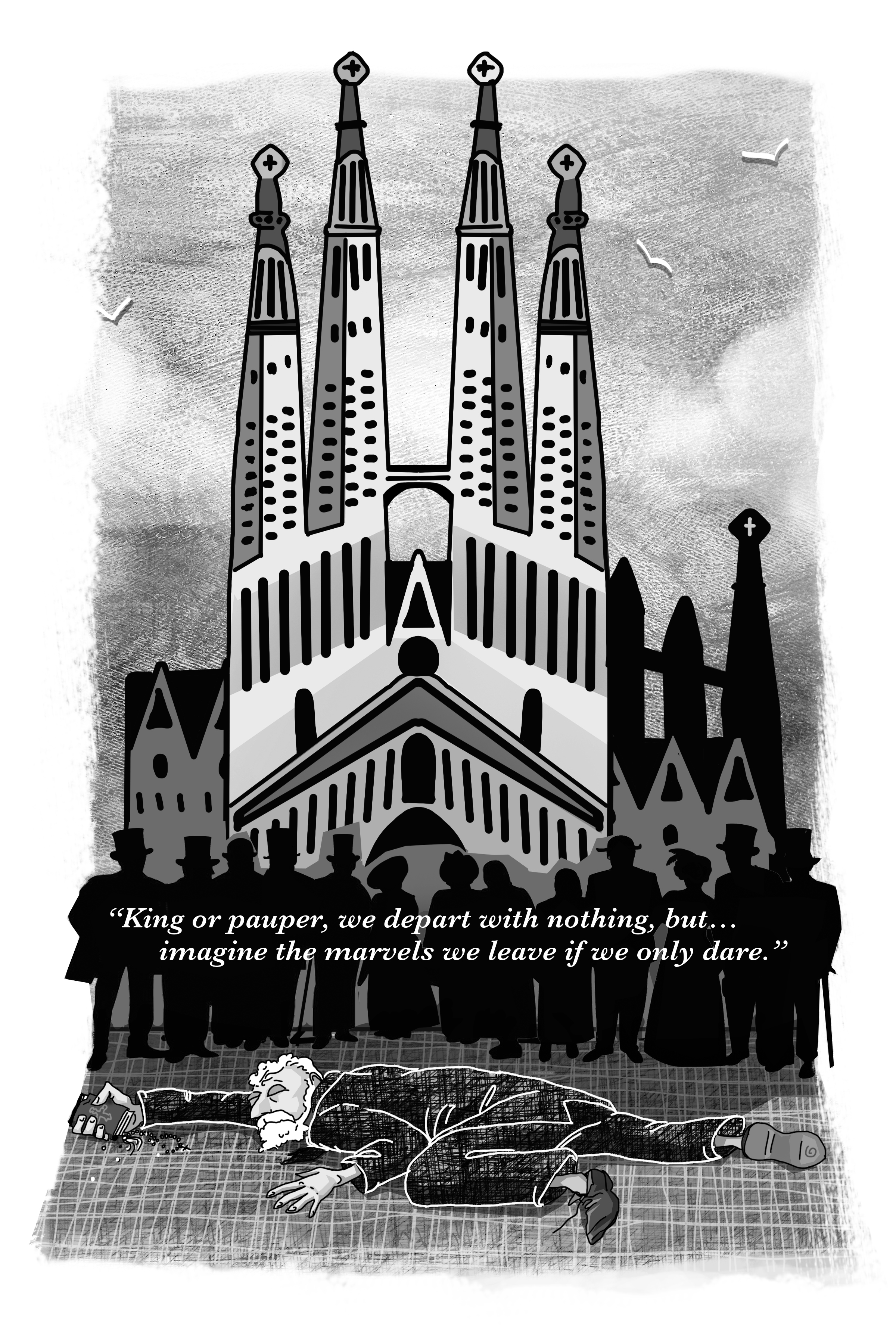

A tram struck him down one evening on his way to inspect the work-in-progress at the Sagrada Família. No one recognised the old man in dishevelled clothing. As he carried no identification papers, he was presumed to be homeless, taken to a paupers’ hospice and left to die. On being given his final rites, the man was recognised by the priest of the Sagrada Família. Antoni Gaudí was interred in the very church he had created — a monument as large as any cathedral in the world, and just as famous. Citizens of Barcelona thronged to his funeral to pay homage to the most universal architect the city had ever known. It was 10 June 1926.

An article I read on Gaudí piqued my interest beyond the Dalíesque nature of his work — the self-absorption in his craft to a point where what he wore didn’t matter to him; the fierce patriot, never leaving Barcelona, never accepting an assignment out of town; his foolhardiness in building an edifice that would take a hundred years and still be in the making; the absurdity of committing his all to a venture when he had neither the funds nor the resources to complete it. This, all at a time when Gaudí was comfortably off — accepting generous commissions yet refusing any that didn’t interest him.

Why, at the peak of his career, take on an unheard-of, costly project that would earn him nothing — one that would constantly drag him down, patching together piecemeal sums to continuously resuscitate his beloved vision?

Now, a hundred years after Gaudí’s death, my family and I were on a bus accompanied by a guide, on a pilgrimage to his still-unfinished masterpiece.

“Imogen, why are we travelling so far from the city centre? The area’s getting rougher and rougher.”

“Gaudí came from the working-class quarter of Dreta de l’Eixample, far from the opulence of La Rambla. He wanted to create jobs for his impoverished community.”

Our bus came to a halt.

We disembarked and stood to attention. The Sagrada took their collective breath away, holding it for some considerable time. Deemed Gothic, the architecture wasn’t flamboyant or grotesque, nor did it bow to the gravitas of feigned piety. Between the giant stork-like cranes, eleven spires shot up, with seven more to come, representing the twelve apostles, the Virgin Mary, the four Evangelists and, tallest of them all, that of Jesus Christ.

Upon entering, we craned our necks to the roof, which hung 456 metres above us. Thankfully, Imogen let us wander on our own while she took a break. “Get a feel for the place. Let’s meet back here in thirty minutes. I’ll answer all your questions then and point out some sights you may have missed.”

My two boys, of course, chose to climb the 504-step narrow, spiral staircase to the roof. They sprinted up the first twenty steps and disappeared. Laura froze. Her hand clutched her heart. Imogen assured her, “The boys are quite safe. They’ll learn to hold their palms against the enclosed walls, which form the innards of an enormous snail — in sync with Gaudí’s whimsical melding of architecture and nature. The steps represent Christ’s march to the cross.”

Laura retired to the crypt to find Gaudí’s tomb. Her husband remained by the bronze, seven-metre-high Door of Glory, fascinated by the Lord’s Prayer etched upon it in more than fifty languages. At head height, I instantly recognised my childhood Swahili. Laura’s Philippine Tagalog was close by. On a wall beside the door, my eyes fixed on a magic square — a series of numbers in four-by-four squares. Each row, column and diagonal added up to 33 — the age Jesus is believed to have been crucified. Three is also the symbol of the Holy Trinity in Christendom.

In thirty minutes, the boys were back. “Wow! That was really cool. You should have seen the view from up there.”

“Did you take pictures?” I asked.

“Yeah. We’ve already forwarded them to our friends. We’ve got a roaming plan.” What they were on about, I had no idea. I’d roamed enough for the day.

Laura swept up beside me. “Hon, look at the pictures I took.”

Imogen recommenced her tour. Instead of dour looks of boredom, she was inundated with questions. Most came from the boys, with a sprinkling from Laura.

Hand-in-hand, we walked together in reverence between pillars representing massive trees in the forest. Sunlight poured through stained glass windows onto the sparkling white marble floor. Each window reflected a different set of colours as the sun journeyed through the day, shining from one to the next — accurate enough to tell the time by.

As we left, I mentally tipped my hat to Gaudí, reflecting that we enter the world with nothing. King or pauper, we depart with nothing. But imagine the marvels we leave behind — if only we dare.