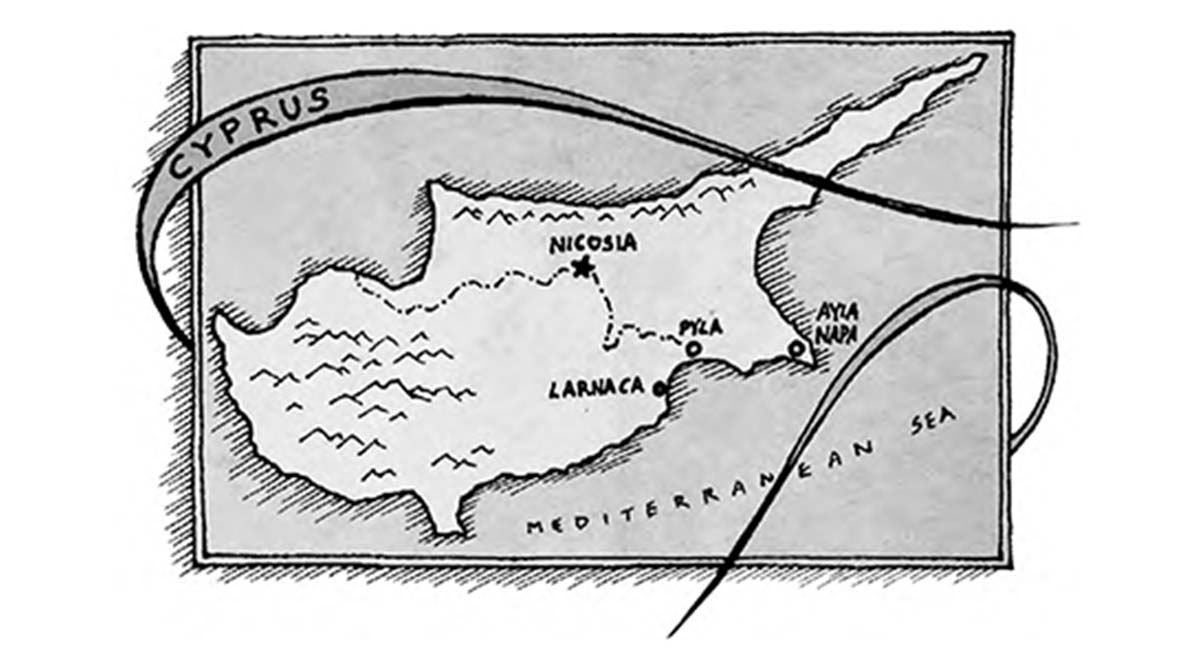

The scene—a warm, sunny summer Sunday afternoon, amid a chorus of homespun English accents—could have been anywhere on the coast of Cornwall or Devon. But it wasn’t. This narrow strip of ochre sand peered out at me from the far corner of the English Forces Base, Dhekelia, Cyprus, a half an hour’s walk from Pyla, my home base.

“Anything else you need, luv?’ the waitress asked. I had just completed my lunch of cod and chips with mushy peas. It was Sunday and the volunteer-run café was closing early. I shook my head, paid my bill, and began to follow the coastline to Pyla. The sun seemed to have been waiting in ambush for me. It really was too hot.

A dilapidated shack stood in front of the guarded entrance to the base, scrawled on its side wall was a crude depiction of a knight in silver armour mounted on a palfrey, a lance cemented horizontally to his hand. A foot from him, a dragon spat fire. A sign to one side read “St. George’s Taxi Service”.

What else could it be called at such a location? It was no surprise that on Greek Cyprus, attached to Britain for centuries, St. George was also its patron saint and boys (especially, I found, with taxi drivers) inevitably were named George.

Under a covered awning stood a luxury Mercedes Benz sedan— a grand tradition of the island’s taxis, which were all Mercs.

The sedan was spotless, a miracle in this heat and dust. It gleamed, reflecting its owner’s pride and fervour. Its back doors had been flung open. A revolving fan on a stand, wired to a plug in the shack, blew intermittent, barely cool air at the defenceless Saint now lolling in the back seat. In contrast to his sleek and polished steel, the 300-lb man was shirtless. His chest hair sprouted like fur through his dirty white mesh undervest. He snored deeply, every now and then futilely waving an arm at random to deter the whining mosquitos that circled ever closer to him.

Children in hand-me-downs played marbles away from the shade and the whirring fan, directing them at a hole in the dried-up mud that their hands showed they had dug. They must have been told to keep well away from his vehicle, no matter what.

I coughed slightly, hoping to wake St. George up. No luck. Tapping the Saint’s shoulder, he woke up, looked at me bug-eyed as if to groan “Who in their right mind would wake me up on a Sunday afternoon?” A pregnant moment later, he seemed to realize it was another bloody tourist, a seasonal and expected pest to add to the mosquitos. He got out, straightened his trousers, put on his shirt, patted his hair ineffectually and bid me enter.

“Ten euros to Pyla,” was all he said.

Eyeing St. George warily, I remembered Pop, my mouse-like English foster dad. Pop would come home from work, remove his “Andy Capp” and white shirt, then, still in his white mesh undervest, wash himself down at the white enamelled kitchen sink (hot water was boiled for a bath only once a week on a Saturday). His supper concluded, Pop would retire to his favourite armchair to snooze and snore like a lord, occasionally waking up to catch a bit of his favourite programme, “Survival,” a show about animals in the wild. To the rest, he was oblivious.

“Ten euros,” St. George repeated, waiting for his confirmation.

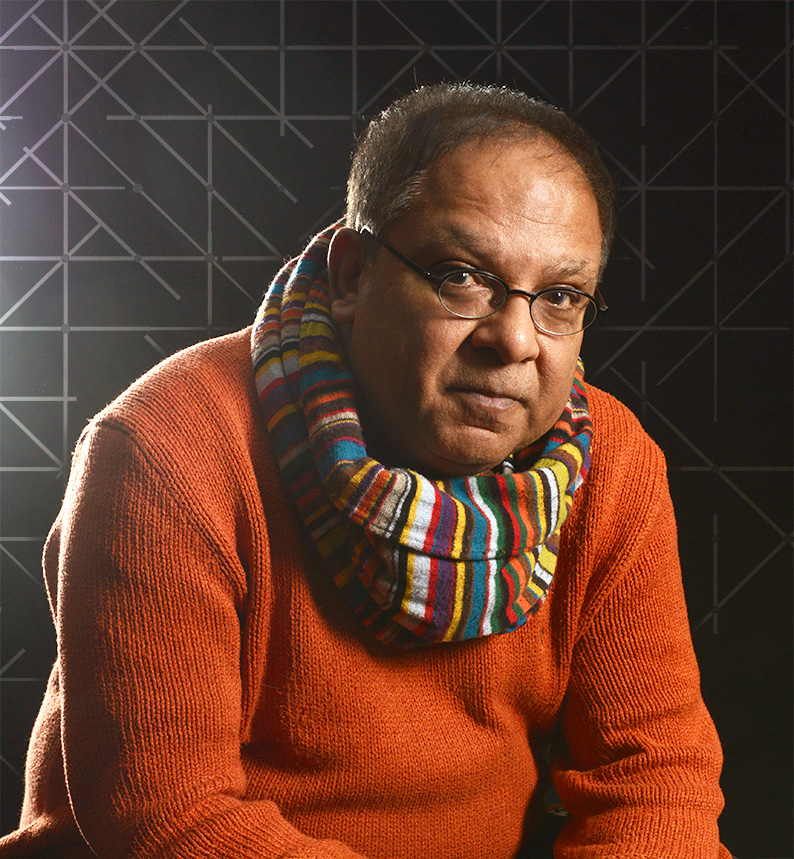

I realized I’d spent most of my life fighting my own dragons—dead and alive—trying my best to escape the clutches of one or another as simultaneously, I fought the slothful saint within to doze off in resignation to their vociferous claim upon me.

“Ten euros?”

What was I getting myself into?

Beyond the purple bougainvillea, sheltering trees and barbed wire gate of Dhekelia, public beaches sprawled alongside the whole stretch of southern Greek Cyprus. Today, what the tourists shunned—barricading themselves in their hotels to sip and nibble beside their palm-fringed pools (everything closed down on Sunday)—the locals embraced with abandon. A carnival atmosphere prevailed. Hordes of children chased down a football or competed for space to play badminton and volleyball. Elderly women sat in a circle, covered head to toe in long skirts, dark blouses, and headscarves, chattering away; middle-aged women wore knee-length shorts or modest swimwear; only the youngest children ran around in swimming trunks and bikinis. The men had sequestered the cooking equipment and stood readying the food, talking quietly to each other while smoking or drawing pipes in and out of their mouths to emphasize their conversation. I lowered my window a little. The aroma of barbequed chicken and fish hit me full-face.

Well-trod footpaths divided the road from the beach. These had been taken over by vendors of ubiquitous freshly cut slices of watermelon, which they handed out of blue and white plastic coolers filled with ice, along with cold drinks, at a fraction of what the shops charged. Smiles and waves beckoned me to join them, the same way my own uncles had smiled and waved me to join their scratch cricket teams on baking Sunday afternoons spent on Kunduchi Beach in Africa as a child.

Unlike here on Dhekelia Road on a Sunday, where locals dominated the beaches, there had been no sign of local Africans on Kunduchi Beach, save as accompanying servants or village urchins peering from behind sand dunes to watch the muhindi.

“Ten euros to Pyla.”

Beyond this curt demand, the Saint parried away all my attempts at conversation in total silence, as though pouting.

As I gazed out at the revellers on Dhekelia Beach, I saw myself back on Kunduchi, where a native boy had peered at me from behind a sand dune, much as I had spent my life peering out at the alien world around me, trying in vain to understand and manage it.

And so, I oscillated between the past and present—the past so dangerously more real.

“Sandy Beach Hotel! “St. George’s voice pierced my reverie, yanking me back to the here and now.