Gnawing hunger woke me up. I opened my balcony to the Mediterranean. Although evening had crept in , its cooler air hadn’t. I skipped down the marble stairs to the lobby.

A waif-like concierge looked up at me, her high heels and ramrod back not quite giving her the authority she demanded.

“ Where can I find a restaurant?”

“ The Shambalaya, just down the road…but it’s high-class Indian,’ she added, inspecting my dishevelled appearance with disapproval.

High-class Indian. My mouth watered, remembering the hand-made dhebras – flour cakes- my nanima would made specially for me. How hurt she was when I didn’t finish them off in one sitting. Perhaps the Shambalaya would make me my favourite dish-masala fried fish with fried potatoes and kedgeree which I had been craving for since her death.

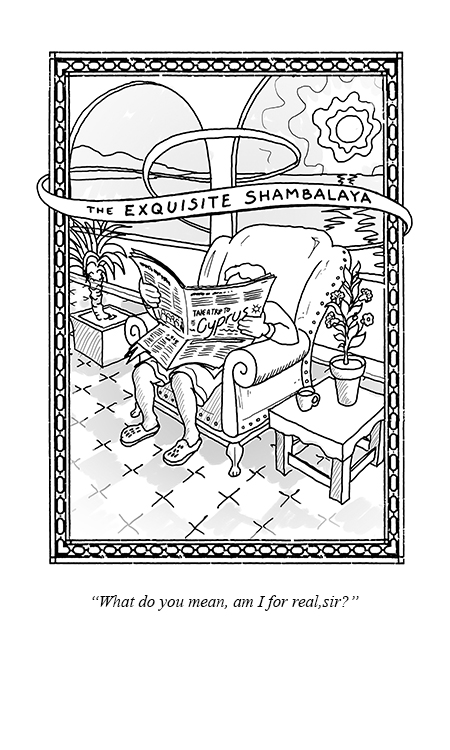

The Shambalaya stood like a Victorian grande dame in mourning, its austere silhouette darkening the shoreline. Too late, I remembered the concierge’s words-“high-class” -and today of all days was Friday, the busiest for the restaurant. I had neither shaved nor showered. I still wore the same shorts I had worn for two days. My sweaty T-shirt clung to me like it would never let go. Dust and sand had greyed my golden Crocs , scarring my feet.

A tacky, flickering orange neon sign hung on the grimy wall above its entrance. Unlit steps led down to a basement. In the unaccustomed gloom, a nymph appeared carved in obsidian. Of a sudden, she sprang to life.

“ Can I ‘elp you?” she asked in a sordid East London Cockney accent. This wraith, no more than my shoulder height, sported a short, short black mini-skirt and black satin top. Her white powdery make-up contrasted sickly with her cropped black hair. She had a black satin shrouded sisterhood at her beck and call, to whom she handed me off to be led in the semi-darkness through a maze of teak tables, intricately laid with glimmering crystal and cutlery. The heavy scent of frankincense candles pervaded the air, their flickering flames reflected in the jewellery, satin and silk worn by the Shambalaya’s ever decorous patrons, parading to and from their designated rendezvous. Passing a gilded mirror, I observed my image with dismay. My hair, apparel nor footwear came close to competing with that of the present company. My unshaved chin began to itch.

I was finally laid to rest in a cubby hole beside a storage room, where I was promptly forgotten. My stomach continued to rumble as I tried to gain a server’s attention. I felt like a parcel dropped off in a corner, waiting to be picked up the next day.

My eyes swept the room, taking in the gaudy rendition of “ high-class” in this village and remembered my father, who owned no car, waving and whistling as we stood by the roadside for someone to stop and give us a ride, which in our small town they always did; my nanima whose husband had been killed and robbed after a lucrative card game, raising six kids, throwing metal weights at them if they misbehaved; Missionary Abu Ali, who was commissioned to knock some religion into me each summer; the continuous friction between the Africans and Asians, evinced by recurring robberies and violence. This, while my fellow diners strutted about displaying their finery, caught forever in their own reflection.

A shimmering movement caught my eye. Through the gloom, a mirage wafted towards me- a young girl carrying a pitcher of water to revive me. The only Indian in sight. Her height and slimness, the lilt of her body, brought back such images of long-lost cousins, now scattered across the world, that my eyes welled with tears.

“ Are you for real?” I questioned.

“ What do you mean, am I for real, sir?”

“ Are you a real Indian ?”

“ Yes. I’m from Gujarat.” She bore no evidence of Cockney heritage, not even in her speech.

Gujarat! My ancestors had migrated from there to East Africa, where I had lived so many lifetimes ago.

“ And where are you from, sir?” she asked innocently.

Her question threw me for a loop. I didn’t think of Canada, where I had married and raised a family for thirty years, nor of England, where I had lived for the previous twenty. Instead, the water-carrier’s voice carried me back, as a boy in Africa, to a marble prayer hall beside a harbour, its floors covered in rush mats. Its shutters open to allow in the sea breeze, and a girl singing a lullaby of hymns to soothe and comfort me.

The water girl stood beside me, patiently waiting for a reply.