A few years ago, a friend of mine, a director of Calgary Economic Development, called me up. “We have an American Ismaili Muslim business delegation visiting us for a week. Can you act as host. You’re an Ismaili and a local businessman.”

“What do you want me do with them? I haven’t been to mosque in decades. I’m married to a Filipina and my kids are Roman Catholic.”

“Just show up at the Glenbow Museum on Monday …and wear a suit.”

The last time I wore a suit was years ago at a wedding. All I wore now were jogging pants and a hoodie.

“And be there by 8.30 a.m. to greet everyone before the Mayor arrives at nine.”

Forty people packed the small conference room. Each wore their best suit or dress and sat down promptly at 8.55 a.m. to receive the Mayor who was one of their own—an Ismaili.

9 a.m. came and passed. By 9.30, delegates were scowling at each other, perpetually glancing at their Rolexes and Piagets. You could tell they were thinking “this is so un-American.” A female executive in a sheer black-lustre skirt and dark Ferragamo jacket, twiddled her white, pearl necklace in exasperation. An hour later, as they collectively exhausted their texting, someone announced the Mayor.

They all looked up but couldn’t see him.

A diminutive figure stood before them. He was wearing a grey and brown Argyll sweater with balls of fluff hanging out from all sides. It looked as if it had been salvaged from a thrift store. He was unshaven. Strands of his hair ran upwards in streaks as if he had forgotten to comb his hair.

The delegates were aghast. They stared at each other, comparing wordless notes. Was this a joke?

“Sorry for being late. I just got back from Disneyland.”

The hostility in the room could have been set on fire. Was this really the Mayor—the man they had come all the way to see? Only his skin colour supported that assumption.

Glancing from the Mayor to his audience, I shook my head in utter disbelief. The whole tour, including this meeting, had been choreographed for months and to the minute. In one sentence, the Mayor had thrown a bomb into the works. My neck began to itch uncontrollably in its effort to break loose from its tight shirt collar.

His Worship continued, addressing an audience that had paid thousands of dollars to be here, each with the potential to invest millions into his city.

“Every year, we take kids to Disneyland as part of the ‘Make A Wish Foundation’ for terminally sick children. Our sponsors can only fly us out at four in the morning and deliver us back the same time the next day. Unfortunately, we were delayed at the LAX airport for hours. I also had to stop at a high school on the way here to give out awards to students for outstanding service to their community.”

For a moment, the female executive stopped twirling her necklace. A number of her colleagues who had been furiously tapping at their smart phones, as if in the midst of texting their complaints to the organizer, also stopped abruptly to look up.

His Worship blurted out an ad lib speech of welcome. If his oratory stirred any of his congregation, they showed no sign of it.

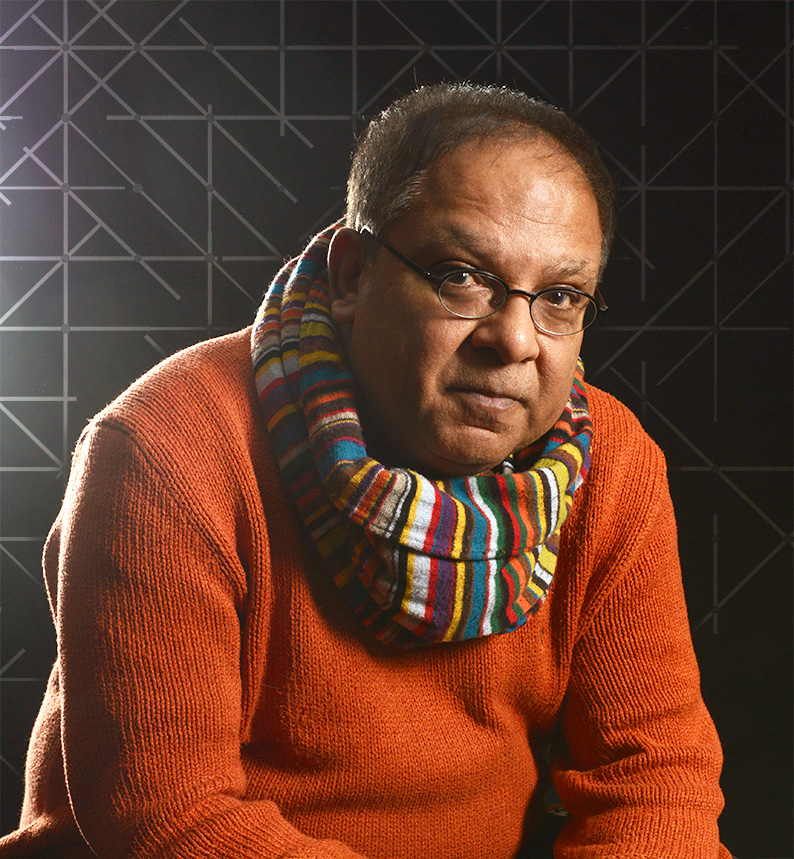

Naheed Nenshi shook hands, accepted a gift, then perfunctorily participated in a group photo before promptly leaving, never once acknowledging their common connection to Islam.

I sat in a stupor as the Mayor exited the room. My feelings toward him swung back and forth like a pendulum. Why hadn’t His Worship made the most of this opportunity to trumpet his religious and social connection to his audience? Didn’t he care? Why hadn’t he spent more time glad-handing the crowd? After all, he was a politician. It didn’t square up. For the life of me, I just could not connect with him.

A year later, my father died. One month thereafter, as was custom, I came to his grave to mourn and pay respect. Dad was buried in a lonely corner of the Garden of Peace on the outskirts of town. The acreage of land was so new, that not a fence broke the view of the endless prairie. A boundless blue sky came to greet it at the tip of the farthest horizon.

The bitter wind slapped my face. There was no shelter to turn to. In accordance with Ismaili ritual, a joss stick had to be lit and planted in front of my father’s grave to purify the air and ward off evil spirits.

There was no headstone—only a slab of granite two feet by one, laid flat upon Dad’s grave, identical to the others. Trying for the umpteenth time to light a match to ignite the joss stick, a hand came out of nowhere to cup the flame.

It was Mayor Nenshi standing beside me.

Both our fathers had died within days of each other and buried side by side. We, their children, had come and gathered here on a peaceful Sunday afternoon without pomp or circumstance to pay them homage on a desolate patch of alien ground so many continents away from their homeland in Africa.

The Mayor had lent a hand to a fellow compatriot while no one else was watching.