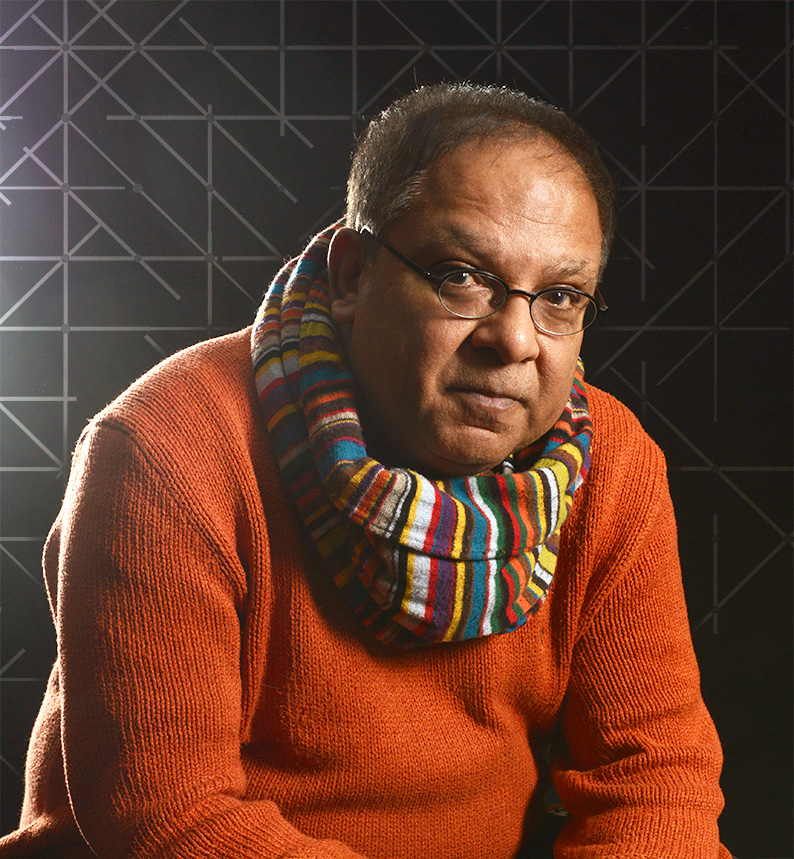

Recently, I was interviewed for a programme called “True Calgarian”.

I examined my brown skin while listening to my incorrigible British accent, forty years on. “Truly Calgarian? Me?”

Since I was taken from Africa at the age of five—my mum obtaining a divorce and whisking me to England with her—I considered Dar-es-Salaam my home. It was a place to return to as soon as possible.

That closeness was strengthened by my father, who stubbornly remained in Africa. Dad worked for an airline, and every school break saw me aeroplaned off to Dar-es-Salaam to rejoin my father and the rest of our extended family.

Imagine, at the age of five, being within the loving embrace of a large number of aunts, uncles, and a dozen cousins, and suddenly, with no explanation, being carted off to another continent.

My mother collects me at Heathrow, dumps me with an English family, and leaves immediately for work. From a world of browns to a world of whites; from a privileged middle-class family with servants, I came into a working-class family in a low-housing council estate—the only coloured person in an all-white community. Curious, people asked me whether Tarzan had been my neighbour.

Despite my English family loving me more than anyone could, my heart belonged to Africa. Every day that passed brought me closer to the day I could leave for home.

The belief of being a stranger in a strange land was entrenched by the behaviour of those I met while training as an accountant. I was now “elevated” from the working class to a milieu of the middle class. In my council estate, I was accepted as one of them. In training, however, I found the deep prejudice that judged me on how I spoke, not on how I behaved or performed. As much as I could not part with my accent—which betrayed my origins—so much I remained out of the fold. The middle class in England is hospitably polite. Beware the Perfidious Albion. All the overtures of welcome never allowed me into a staff birthday party, let alone the workplace squash ladder.

Having reached my glass ceiling upon qualifying as an accountant at 24, I embarked upon a second diaspora to Canada.

I already had a Tanzanian passport as well as a British one. The latter allowed me to work in any British territory abroad and even in Europe. The plan was to secure a job in Canada, reside there for three years to obtain a passport. It would leave me, aged 27, with access to any advanced country in the world, brandishing four international accounting designations.

Why Calgary?

My Muslim Ismaili family and friends were booted out of East Africa with a week’s notice, carrying one suitcase as a memento of 150 years of history on the continent. Thanks to The Honourable Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau, my people were given the privilege to settle in Canada. The French-speaking out of The Congo landed in Montreal; the rich escaped to Vancouver; my family, with neither recognised qualifications nor wealth behind them, found themselves in various ghettos in suburban Toronto, eking a living out of shift work in factories.

Calgary was the only place in Canada where I had no relatives and could live an independent life—my mum now a millionaire in England, my father, the only East Indian in East African Airways, decided they were happy to remain where they were. Having been brought up as one-third atheist, one-third Anglican, and one-third Ismaili Muslim, I belonged to each, yet to no one, desperately needing space to discover who I really was.

In the late 1970s, Calgary boomed, thanks to swimming in oil the world needed. It shone with the promise of dreams fulfilled if you applied yourself. The city’s lifeblood was its entrepreneurs.

Despite her lack of English, her atrocious accent, Mum became a millionaire through working seven days a week and investing little by little in real estate. I wanted to follow her path. She had no education. I was qualified with a well-paying career and an entree to the successful clients of my firm.

Yet, my mindset was still to leave Calgary within three years. My one-room bachelor suite of 400 square feet was a camping ground—a sleeping bag, a boombox, an Ikea folding table and chair. That was it. Easy to pack up, easy to move on.

Three years turned into four, then five. It never stopped me from dreaming of my African home, sans family, sans community.

Me, a true Calgarian?

Ten years passed. On a plane returning from Christmas in LA, I contrasted the deathly darkness of the City of Angels to that of Calgary laid below me, literally exploding with light.

Without forethought, I exclaimed, “Ah, home at last.”

England restricted me in every way, for reasons such as my accent and pedigree, which I could never overcome unless, like my mother, I worked in the sewers for 80 hours a week, forsook all joy and rest to save and invest.

Calgarians—mostly from abroad—couldn’t care less about your accent. You were judged on your performance. The values the English accumulated over centuries were superfluous here. This city allowed you to carry out your dreams. I did. Many turned into nightmares—stock crashes, commodity losses, the booms and busts of an oil economy. But the city gave me countless chances to redeem myself and find further opportunities by learning from my mistakes. Even today, I’m pursuing new horizons—writing as a vocation.

What did I miss the most about my home in Dar-es-Salaam? My close-knit Ismaili community, my sense of belonging.

Here in Calgary I began, through happenstance, to cultivate a circle of Jewish friends. Gary, my co-worker, became my best friend. At a cinema, I bumped into the Benjamins. I left my accounting firm to join a Jewish property mogul and was taken into the family of 82 joint-venture partners—almost all Jewish. During the bust of 1982, I audited third-year law school to brush up on financial instruments. I sat beside a bemused student, Ali, a Lebanese, who became another valued family friend. Joining a Scrabble club, I met Siri, a Sri Lankan, instrumental in making our club the largest in North America. Jacques, a Frenchman, helped look after my mum when she finally emigrated, then turned blind. I married a Filipina. Some clients—Pakistanis—became close friends and business partners. Today, I can boast that whatever advice or service is needed, or associates to fulfil a contract, they are all a phone call away.

The close-knit, esoteric Ismaili community I dreamed of returning to in Africa has now become an international exoteric community of friends in Calgary. Friends I would regard as family.

One summer, when my boys were teens, we took them to Hong Kong. “Pops, where is the Canadian embassy?” they asked.

“Oh! My goodness. You haven’t lost your passports, have you?”

“No!” they retorted. “It’s Canada Day and we want to participate.”

It took two generations to discover home, as witnessed by my boys’ ask. In their minds’ eye, they were true Calgarians, utterly Canadian. Nothing else. After years of flight, we had finally landed home.

Thank you, Calgary. Thank you, Canada.